My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? Why are you so far from saving me, from the words of my groaning?

Psalm 22:1

I can’t quite remember how, but when I was a senior in high school, I stumbled upon a song called “Perth,” and it changed the way I listen to music. I was captivated by the raw, multi-tracked vocals and strangeness of the lyrics, the dissonance of the lead guitar riff, the double kick drum catharsis with that glorious horn chorale soaring high above it all. It was one of a few category-shattering moments in the development of my musical palette where I thought, “What in the world am I listening to?” And I couldn’t articulate how or why, but I felt in that moment that Bon Iver’s music is deeply spiritual.

It’s embarrassing (and laughable) to admit, but at the time, I never bought any music without reading all of the lyrics first. I was a self-appointed zealot who spent most of his adolescence crusading against anything deemed secular. This is in no small part due to my undiagnosed religious OCD, which mostly manifested in an irrational, all-pervasive terror that any wrong I committed could earn me (or others) a one-way ticket to hell. Of course, I was never taught this, but the overactive imagination of an anxiety-prone teen is fertile soil for the even the smallest thorns of fear, even as I was surrounded with people who gave me nothing but love and light.

I eventually got over the fact that Bon Iver’s self-titled record contained some choice words and, with some trepidation, gave the whole thing a try. The curiosity sparked by the beauty I found in “Perth” was stronger than my fear, so I swung wide open the door.

I didn’t pay much attention to the lyrics of Bon Iver at first. It was a new listening experience for me, because it was the first time I realized that words and syllables can be musical in and of themselves. I used to think of songs sort of like essays, simply conduits for a specific message or narrative. This album changed that; I was finding profound meaning in lyrics that seemed opaque, impossible to parse. I didn’t feel a need to “figure out” what the songs were saying, but I knew that they resonated deeply, and that was enough. These songs were places I could visit; I felt like I could step through the album cover into that impressionistic Wisconsin countryside and drink in the infinite evergreen air. And though I had no idea what its lyrics were about, I thought “Beth/Rest” felt more like a worship song than anything that passed for one on the radio.

Speaking of evangelical Christianity, as one who has spent most of his life thoroughly enculturated in it, the way I experience the world has always felt a bit Christ-haunted. Flannery O’Connor wrote a novel called Wise Blood, a marvel of Southern Gothic fiction which follows the misadventures of Hazel Motes, a tortured, self-proclaimed prophet of anti-religion. In her preface to the 10th anniversary edition of the book, she described Jesus as “the ragged figure who moves from tree to tree” in the back of Hazel Motes’s mind. That imagery makes me shiver.

I thought myself to be a pretty stalwart Christian when I first discovered Bon Iver. Throughout the years, my faith has transformed, dilated, disintegrated, blossomed. Sometimes it disappears completely. But I have always seen Christ everywhere, even when I don’t want to.

I write all this to say that once I started paying attention to Bon Iver’s lyrics, I found a whole host of phrases that jumped out at me. Figures hiding behind trees. And for this typically angsty teen, it seemed like whoever wrote those lyrics understood the religious unease that followed me closer than my own shadow; they knew what it felt like to be haunted by God.

I don’t at all presume to know what Vernon believes or what his religious background is. This is a story about how I’ve personally encountered his work through the lens of my own spirituality. That being said, Vernon majored in religious studies at the University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire, and it’s safe to say that bits of this esoteric knowledge have surfaced in his lyrics. He has said as much in interviews, once noting that, “When you use enough of that language, it perks some people’s ears up… I do love those words, I love the word consecration, these holy words so to speak. I like using them in a way people haven’t heard before, or right next to a bunch of swear words. It’s just fun — it puts a smile on my face.” While a statement like that might seem cavalier, it seems apparent that Vernon isn’t a provocateur for the mere sake of it. “For me from a very early age, music has been my religion,” he says in the same interview. “It’s been my way of understanding, it’s been my way of celebration, it’s been my way of contemplation.”

And this begs the question: what makes these songs so different from psalms?

Today is Kumran

This fascination with “holy words” seems to span Bon Iver’s whole body of work, to varying degrees. When I first took notice of it, I was reading the lyrics of “Re: Stacks,” the closing track of For Emma, Forever Ago.

This my excavation and today is Kumran

Everything that happens is from now on

This is pouring rain, this is paralyzed

Kumran is a misspelling of Qumran, a settlement in the West Bank nearest to the excavation site of the Dead Sea Scrolls. In a 2009 interview, Vernon shed some light on the metaphor, saying, “When they found [The Dead Sea Scrolls] it changed the whole course of Christianity, whether people wanted to know it or not. A lot of people chose to ignore it, a lot of people decided to run with it, and for many people it destroyed their faith…”

The metaphor frames the introspection of For Emma, Forever Ago as a sacred discovery, a courageous artifact of self-examination, a mile marker after which nothing can be the same. It’s a metaphor that regards music making as something akin to a sacramental endeavor, a mysterious grace that is able to transform its participant.

After this realization, the religious language in Bon Iver’s music seemed almost inescapable to me.

“Seminary sold.”

“So many Torahs.”

“Water’s running through / In the valley where we grew to write this scripture.”

“Oh, the sermons are the first to rest / Smoke on Sundays when you’re drunk and dressed.”

“Heavenly father / Is all that he offers / A safety in the end.”

And the allusions became more obscure. The song “Hinnom, TX,” shares a name with a valley in Jerusalem known as Gehenna, where, according to Hebrew Scripture, ancient kings sacrificed their children by fire. It became known as a place for the wicked, and was subsequently translated as “hell” in the King James Version of the Bible.

Here Vernon appropriates the word that conjures thoughts of fire and eternal suffering with some creative lisence. For Vernon, maybe Hinnom marked a particularly “hellish” time in his life. In this sense, I suppose Hinnom could be anywhere. Including, perhaps, inside of us.

Long lines of questions

I wandered my university campus with these songs in my ears for a couple semesters, through the library doors into the sunlit foyer, tossing apologetics textbooks into my backpack. Any desire to catch up on my schoolwork was sabotaged, rendered irrelevant by some sort of manic appetite.

Attending an Evangelical university had immersed me into a community of different kinds of Christians for the first time (I know, this hardly passes for any kind of diversity, but this was a big change for a kid from a wink of a town in the Montana countryside), and suddenly, everything seemed complicated. If we were all after the same truth, why did we have such a hard time agreeing on anything? If we all worshipped the same God, why all the division? Couldn’t a wise, loving, all-powerful creator just make this stuff clearer in the first place? I had a lot of questions, and for reasons I couldn’t articulate, I needed answers. In retrospect, I could blame it on rationalism, René Descartes, or the 2nd Great Awakening, but whatever the case, I knew that doubt was shameful for a believer; the death knell of feeble faith. And now that the waters were rising, anxiety was poised to devour me whole. I was bailing out the boat the only way I knew how: I had to prove the validity of my worldview. I needed it to be true. Certainty was the air I breathed, and it was a heck of a drug.

In many ways, it was the perfect time for an album about uncertainty to enter my life.

One day that fall, I made an exciting discovery while perusing my usual music blog haunts: the Bon Iver website had been updated with an essay, an album announcement of sorts, written by Justin Vernon’s longtime friend and collaborator Trever Hagen. An excerpt:

22, A Million is thus part love letter, part final resting place of two decades of searching for self-understanding like a religion. And the inner-resolution of maybe never finding that understanding. When Justin sings, “I’m still standing in the need of prayer” he begs the question of what’s worth worshipping, or rather, what is possible to worship. If music is a sacred form of discovering, knowing and being, then Bon Iver’s albums are totems to that faith.

Reading this was electrifying for me. It felt like a confirmation of all of my suspicions and hopes about Bon Iver and gave me reason to believe that 22, A Million would be my favorite album yet.

On August 17th, 2016, two new songs were released and the tracklist was revealed.

It’s hard to articulate just how I felt in that moment. It was equal parts apprehensive and invigorated, the kind of muddled emotional cocktail one experiences while reading a banned book or trespassing on private property. I watched the lyric video for “22 (OVER S∞∞N),” and it knocked the wind out of me. Some songs just feel important. The capitalized “You” in the following lines wasn’t lost on me, nor was the uncapitalized “god” in the curse to follow:

oh, n I have carried consecration

n then You expelled all decision

as I may stand up with a vision………

(caught daylight,

god damn right)

The other single, “10 d E A T h b R E a s T ⚄ ⚄,” was a bucket of ice water, the veritable antithesis of its tender predecessor. With its seismic, heaving percussion and seemingly countless layers of aggressively processed vocals, it was erupting with a frenzied volatility, like the whole arrangement was threatening to collapse in on itself at any moment.

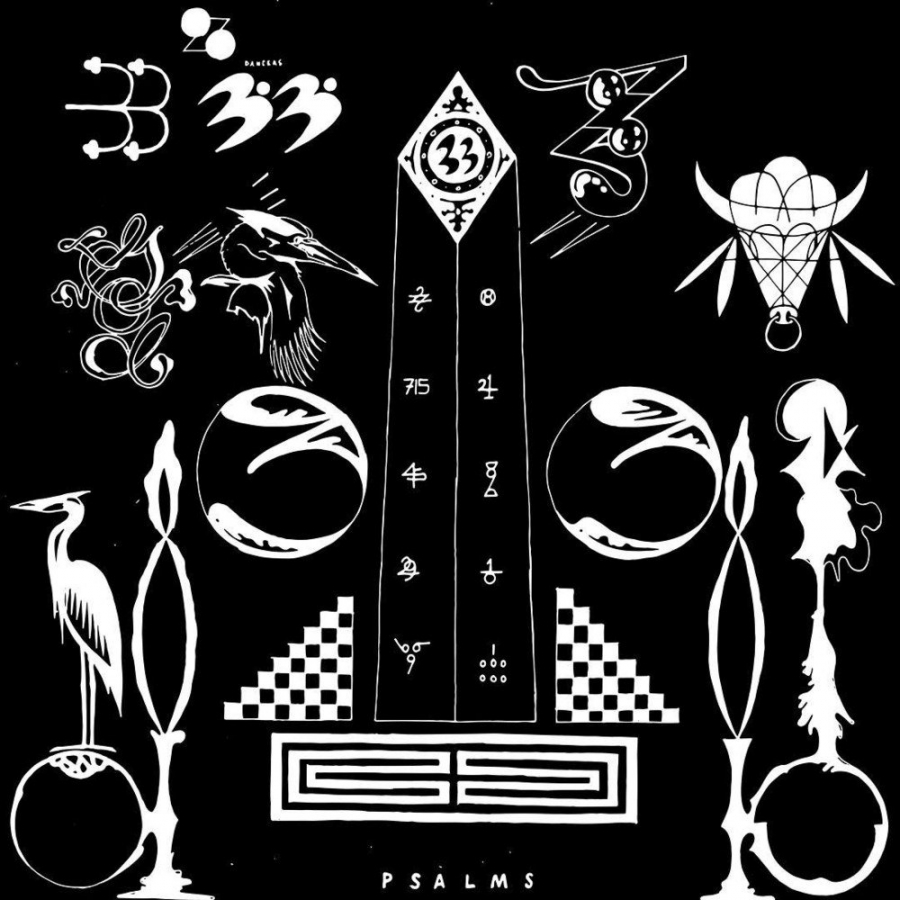

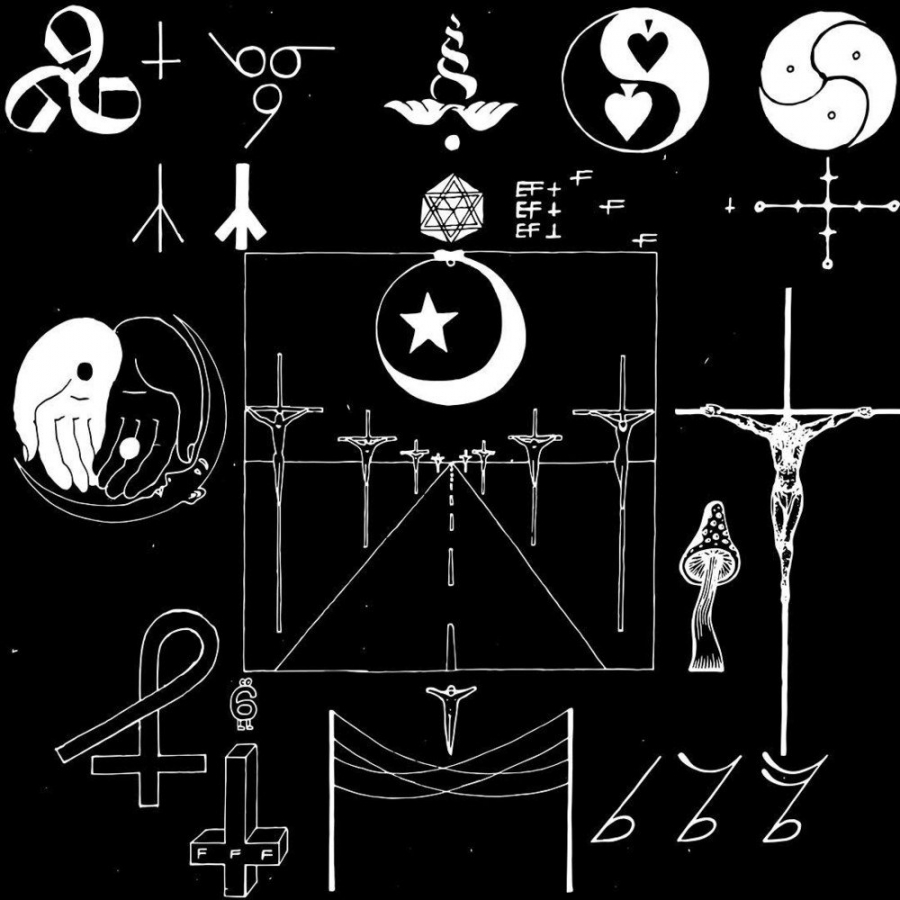

The iconic album cover by Eric Timothy Carlson proved somewhat disquieting to me as well, and it’s difficult to explain why if you haven’t spent some time in the American Evangelical expanded universe.

Serpents, doves, incense, lambs, upside-down crosses, obelisks, yin and yang. It was a perfect hybrid of the sacred Christian iconography I held dear and what I perceived to be the sinister peculiarity of occult symbology, all held together by a pervading sense of Daoist duality. It triggered a sort of cognitive dissonance for me that I couldn’t shake, something like a fight or flight response.

What gave me the most pause was one song title in the tracklist that loomed like a specter in the back of my mind until the album’s official release. The 6th track:

“666 ʇ”

I closed my laptop. I studied the haggard limbs, the dead leaves outside my second story window, unable to deny the presence of that silent phantom. I repeated my prayers softly, waiting for the devil to leave the room.

Unburdened and becoming

When 22, A Million finally came out, I listened to it front to back for the first time.

There were moments that I absolutely loved, but the experience was altogether too conflicted for me; throughout that whole first listen, I fought the inexplicable instinct to tear my headphones out, particularly during “666 ʇ” and the following track, “21 M♢♢N WATER,” which felt like the climax of the record’s descent into oblivion.

It was an utterly unnerving experience. I just couldn’t do it.

It’s difficult to explain why 22, A Million elicited such a violent response from me at the time. I think a lot of it was the religious OCD, pushed to its limits by the record’s paradoxical blend of sacred and sacrilege.

This concept of paradox and duality is a hallmark of the album, which is reflected in the balance of light and dark elements in the album artwork. “666 ʇ” even deconstructs the word “paradox” in an instance of clever wordplay:

That’s a pair of them docks

Mooring out two separate lochs

Ain’t that some kind of quandary

(Waundry)

Pair of docks: paradox. “Waundry,” one of several invented words on this album, also makes an appearance here, presumably a portmanteau of “quandary” and “wander,” describing a state of aimless, endless questioning.

Maybe I reacted so strongly to my first listen of 22, A Million because these lyrics embodied my deepest apprehensions about my own faith: that I was floundering. That all of my “waundry” would only end in quandary, dead ends and fistfuls of sand. That after all, I knew nothing, and nothing could be known. That familiar tension returned, the demon pressing up against my sternum.

And so I didn’t listen to it again for a long while. But some kind of seed had been planted in my anxious little heart, and as my own worldview became more cloudy and convoluted, I found my mind absently drifting to the world of 22, A Million on a daily basis; the symbols, the textures, the numbers. Maybe it was morbid curiosity, maybe it was the sneaking suspicion that this music had something to tell me. But in a fine case of cosmic irony, what I feared most about Bon Iver’s songs was the very thing drawing me back: uncertainty.

My return to the record was tentative. It felt like I was listening to contraband for a while, but in an exciting sort of way. It was like my own form of whacked-out self-administered exposure therapy; the more I listened, the more my anxiety waned, and before I knew it, I was enchanted. With all of its songs in context, 22, A Million resonated more than anything I had heard in ages. I began to notice something that I hadn’t on the first listen, which is that the swirling chaos of “21 M♢♢N WATER” gives way to some of the most peaceful pieces of music in Bon Iver’s discography. It’s a song cycle that takes you through hell to give you a glimpse of heaven, a strangely beautiful post-postmodern tapestry of redemption, complete with a closer that recalls Christian hymns of yesteryear, “00000 Million” (and if listening to it isn’t enough to convince you, the audience received small, hymnal-like lyric booklets for this song during the record’s live premier).

The world of 22, a Million is multilayered and dense, rich with symbolism, metaphor, personal anecdote, baffling imagery and allusion. The meaning of the numerology alone has been the subject of countless fan message board threads. For instance, the number in the title “33 ‘GOD'” likely refers to the 33rd Psalm included in the song as well as the age of Jesus of Nazareth when he was crucified. (Interestingly enough, the Gospels claim that Christ quoted this exact Psalm on the cross as a response to being abandoned by God the Father.) “715 – CRΣΣKS” alludes to the area code of Vernon’s hometown in Wisconsin. “666” is appropriately placed as the 6th track (the same track number occupied by “Hinnom, TX,” by the way). One Redditor even theorized that the lyrics of the song 8 (circle) draw heavily from Dante’s Inferno, with the title referring to the 8th circle of Hell. And at this point, I don’t find it unlikely.

But for me, so much of the beauty of Bon Iver lies in the sense that there isn’t something concrete to be discovered, no equation to be solved. I have no idea what on earth the lyrics of 8 (circle) are actually about. All I know is that when Justin Vernon sings, “I’ll keep in a cave, your comfort and all / Unburdened and becoming,” I feel grateful to be alive. The phrase “unburdened and becoming” has become somewhat of a personal mantra for me. It’s a state of being that I aspire to, and it helps bring me back into the present when my thoughts are dark and distant. I don’t know what Vernon meant by it, but it sure means a lot to me.

The season of my life soundtracked by 22, A Million marked a paradigm shift in the way I perceived the world around me. And while this album was only one of several variables contributing to that change, it played an undeniable role in catalyzing it. Up to that point, I thought that nothing resembling truth, beauty, or goodness could be found outside of tidy borders of my own worldview. Those days, I was more open to being surprised. I was beginning to feel comfortable with those forbidden words: “I might be wrong.”

What is left when unhungry?

A few more times around the sun and a lot had changed. I graduated college. I was about a year’s journey into marriage with my wonderful wife. I was transitioning from a job at a restaurant and trying to find out what the heck I was supposed to do with my life. The world was spinning at an alarming rate, but life was really good. My loved ones and I were thriving, and I had just started working as a maintenance person at our church.

All things considered, it was a strange time for me to start losing my faith.

I’m not sure exactly when or why it started, but my enthusiasm for anything related to my faith began to wane sometime in the months to follow. I truly can’t recall an inciting incident… it was gradual and inconspicuous, like a phantom that had been sneaking around for years finally caught up with me. However it happened, the church went from a place of belonging and peace to one of anxiety and confusion. No matter how beautiful and pure a worship gathering was, I couldn’t switch off my critical faculties. Was I really encountering the Lord alongside my fellow believers in that sanctuary? Or was it all nothing more than pleasant brain chemistry, a state of corporate euphoria in response to stimuli? I became skeptical of my ability to discern any transcendent experience from my own feelings. The liturgy that once refreshed my soul tasted bitter on my tongue. Any attempt at earnest prayer was like pulling teeth.

Sundays became my least favorite part of the week, nothing more than a day to survive. There were several loved ones I felt safe to confide in, but generally speaking, it was an isolating experience. In retrospect, I think there were lots of folks in my faith community that would’ve responded to my doubts with grace and supported me unconditionally, but paranoia prevented me from letting them in. Thus, I kept people at arms length, kept quiet, and tried to carry on as if nothing had changed.

I remember so many Sundays where I lay in bed until the last possible minute, in the grey lowlight of dawn, trying to remember what it felt like to be passionate about my faith, yearning for the zeal that animated my early years as a Christian. It was in times like those, in that bleak haze of apathy, that the song I once avoided out of terror comforted me like a weighted blanket. As I stared at the ceiling and listened to the chickadees in the tree outside our bedroom window, those lyrics would come to mind, a last ditch prayer when I couldn’t bring myself to speak one aloud:

“Take me into your palms / What is left when unhungry?”

If you wait, it won’t be undone

To be honest, not much has changed since then. I still feel trapped in a sort of limbo when it comes to my faith. I often long for the days when things were simpler, when my relationship with God was earnest and uncomplicated. I don’t think there’s any way to get that back.

It was sometime in the middle of my faith transition that i,i was released, the long-awaited follow-up to 22, A Million. I went in with no expectations, knowing that no matter what the record sounded like, I would be surprised. Bon Iver had earned my trust, and I was simply happy to be along for the ride.

I really enjoyed the first few singles from the new album, but when the fourth single was released, it resonated on a different level. It was called “Faith.”

One of the first things that struck me about the song was that it seemed to address religion more candidly than most Bon Iver tracks. Vernon sings of the road he’d formerly known “as a child of God,” a phrase that Christians commonly identify themselves by. As soon as I heard that lyric, I felt as if “Faith” was written for me, and for anyone else who feels like a stranger in a worldview they once called home.

While the sound and sentiment of “Faith” is several shades brighter than the songs of 22, A Million, the theme of paradox remains very much present. In the following stanza, Vernon seems to deny belief in a deity while also insisting that he is a person of faith:

I should’ve known

That I shouldn’t hide

To compromise and to covet

All what’s inside

There is no design

You’ll have to decide

If you’ll come to know,

I’m the faithful kind

Personally, the phrase “There is no design” gives me flashbacks to educational DVD’s, creationism seminars, and apologetics tracts, vanguards of the intelligent design community’s defense against the secularization of the American education system. In the American cultural consciousness, evangelicalism and science are diametrically opposed. In his provocative, iconoclastic fashion, Justin Vernon subverts this association, perhaps winking at the idea that maybe faith has little to do with what we believe and everything to do with what we hope for.

Am I dependent in what I’m defending?

And do we get to hold what faith provides?

Fold your hands into mine

I did my believing seeing every time

The last line of the stanza invokes the old adage “seeing is believing” and turns it upside-down. Believing in light of concrete evidence is utterly unremarkable; you would be foolish not to. However, when it comes to spirituality, I have often been tempted to do just that, thereby reducing the divine to what I’m able to wrap my head around; it’s much easier to mentally assent to a list of prerequisite beliefs than it is to seek the face of God. Indeed, it seems this kind of unshakable certainty about doctrine has become part and parcel with Christianity in the West (I mean yikes, Christians burned other Christians over this stuff). Interestingly enough, Jesus seemed to condemn this sort of approach to matters of faith, saying “…blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.”

In “Faith,” I think Vernon is taking a stab at reclaiming a bastardized concept. Belief with all the answers is not faith at all; it’s hubris. Faith is acknowledging how very little I can actually know about God and choosing to trust anyway. In the words of St. Augustine, “Si comprehendis, non est Deus,” which theologian Miroslav Volf roughly translates this way: “If you understand God, what you understand isn’t God.”

All this time, have I been in bondage to my allegiances? Does “what we’re defending” prevent us from truly engaging with those who are different from us? “Faith” suggests a different way. Instead of hands folded in solitary prayer, we’re given an image of togetherness: hands joined in solidarity. There is a holiness to both, but I would posit that piety is worthless if it has no bearing on how we treat those we disagree with. This is a theme that runs the course of the album, drawing our attention to the here and now rather than a distant, idyllic thing someplace else. Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done, here on Earth as it is in heaven.

I don’t know where I’m going with this. At the end of this directory dump, I find myself tempted to try and tie it all up in a neatly contrived flourish of resolution. I’m really desperate for it all to mean something definitive, if I’m being honest with you. I’m a recovering certainty addict and old habits die hard, I guess. But I’m just gonna treat it like a Bon Iver song; songs aren’t essays, and this isn’t either. This is just a way-too-long, too-serious blog post by another white guy who really likes Bon Iver and thinks that music is like, transcendent, bro.

My files have been transferred. Having nothing left to say, I leave you with this excerpt from “Now II” by the great David Berman:

O I’ve lied to you so much I can no longer trust you.

O Don’t people wear out from the inside,

Why must we suffer this expensive silence,

aren’t we meant to crest in a fury more distinguished?

Because there is my life and there is our life

(which I know to be Your life).

Dear Lord, whom I love so much,

I don’t think I can change anymore.

I have burned all my forces at the edge of the city.

I am all dressed up to go away,

and I’m asking You now

if You’d take me as I am.

For God is not a secret,

and this also is a song.

beautifully written and completely understood. i love everything about this take

LikeLike